Translation Team: Rim Lababidi, Lora Abaza.

During the Syrian war, the country’s antiquities have been exposed to numerous types of violations. The most prominent of these violations was the looting of archaeological objects from museums or monumental buildings in heritage sites, or through illegal excavations of archaeological sites, which caused great loses for the Syrian cultural heritage. These subversive acts come as a result of years of inadequate policies that had marginalized the local community. These policies had unfortunately failed to educate the local community about the significance of the country’s cultural properties and to link the community’s identity to its cultural heritage. During that past period, the Syrian cultural heritage was merely protected by the law under the auspices of the Syrian authorities.

At the beginning of the Syrian revolution and the responses that it had received from killing to displacement and loss of security, the heritage sites lost the umbrella that was protecting them. The looting of antiquities then peaked and it was either a way of reprisal against the Syrian authorities or a source of unlawful gain for military groups. A leading group in the looting and trafficking networks of Syrian antiquities was the Islamic State in Iraq and the Syria (ISIS), which organized and supervised industrial scale operations of looting and trafficking. While in power, ISIS gave a green light to its followers to loot antiquities in Syria and Iraq and to demolish all that they could not steal in a systematic step to destroy the identity of the region on the one hand, and to secure additional sources of funding on the other. This was supported by antiquities trafficking networks that facilitate smuggling the region’s antiquities through neighboring countries.[1]

The Idlib Antiquities Center, supported by local organizations and some administrative and judicial authorities in Idlib governorate, was recently able to confiscate a number of Palmyrene funerary reliefs and to prevent any attempt to sell them. The confiscated objects were deposited in Idlib Museum in order to protect them, and to systematically document and study them.

[1] https://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Le-trafic-d-antiquites-au-Moyen-Orient-du-nettoyage-culturel-au-financement-du.html.

– Greenland, F., Marrone, J., Topçuoğlu, O., & Vorderstrasse, T. (2019). A Site-Level Market Model of the Antiquities Trade. International Journal of Cultural Property, 26 (1), 21-47. DOI:10.1017/S0940739119000018.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

The archaeological site of Palmyra from 2011 until now

The site of Palmyra, like other archaeological sites, has been exposed to sheer levels of destruction, vandalism, and looting. Since 2012, the Syrian regime has located its forces in the most strategic and significant sites in both the modern part of the town and its archaeological park in order to tighten its hold on the city of Palmyra and its residents.

While on site, the Syrian forces made several interventions and changes, which directly impacted the architectural and urban elements of the site. The reports, photos and records published during that period, document the use of this site for military purposes by the Syrian forces which continued until the middle of 2015, i.e., approximately for three years (2012 – 2015).

During that period, most of the damage impacting the site was documented. This damage was mainly caused by opening roads for military vehicles, constructing barricades for soldiers and the stationing of artillery and heavy war machines on site. Unfortunately, during that period, the site was looted and some of its antiquities had gone missing.[2]

[2] http://www.asor.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Palmyra_heritage_Adrift.pdf.

- 1. On the right, an image for soldiers of the Syrian army holding busts in Palmyra, July 2012.

On the left, the same object in the right image, after been confiscated by the DGAM in 2014.

Photo from: Patrimone archéologique syrien en danger

By May 2015, ISIS entered the site of Palmyra and controlled it which exposed the site to probably the worst violating acts in its modern history.

Finding and Confiscating the Looted objects

Palmyra city was and still is one of the most important Syrian cities that date back to the classical period. Due to the artistic, cultural and esthetic values the city possesses, it was coveted by antiquities thieves who took advantage of the city’s isolated location in the Syrian desert and the absence of specialized authorities.

In the period leading up to the takeover of the city by the Islamic State, there were reports indicating the occurrence of violations and illegal excavations in search of antiquities, especially in the necropolis area. Also, several reports appeared to confirm the loss of many objects from the city. At some point, these looted objects reached the black market and some of them started to be openly trafficked on the Internet and social media. Among these objects, we were able to identify a group of Palmyrene funerary relief busts that was transferred to Idlib Governorate through antiquities trafficking networks.

Our team was unable to determine the exact date of the arrival of these looted artifacts to Idlib, but we are certain that they have been in the governorate since 2016, when they were put up for sale and trafficked across the borders. At the time, our team collaborated with the local authorities in order to prevent the selling and trafficking of these looted reliefs. After doing an extensive research, the team was able to trace the traffickers’ network to the city of Sarmada, located on the Turkish border, where we were able to see and examine the artifacts. During this process, our team was able to examine only six objects, and it was unclear whether the traffickers had further objects in their possession or not. Photo documentation was conducted for the six reliefs.

According to information provided by the traffickers, we learned that the provenance of these objects is the city of Palmyra, and that their transportation to Idlib was facilitated by members of the regime’s army through a military route.

2. The looted Palmyrene reliefs, Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center, Idlib 2016.

Despite our success in halting the selling and trafficking attempts of the Palmyrene busts in 2016, we were unable to recover the objects. Talks and negotiations to retrieve these objects were ceased without assuring that they will remain inside Syria until the middle of 2019, when they resurfaced again and they were still in Idlib Governorate. The reopening of the Idlib Museum was a turning point in the story as it provided the required umbrella under which the team can claim these objects and where they can be preserved. In cooperation with the local and administrative authorities, the looted artifacts were confiscated on the basis that they constitute a public property of the Syrian people. The confiscated objects were transferred to Idlib Museum and they were officially deposited in it. They are seven Palmyrene funerary relief busts, and their examination confirms that they are authentic objects that date back to the Roman period and they feature typical Palmyrene sculpturing art.

While examining the objects, no museum or succession numbers were found on them, hence, it is challenging to determine whether these objects were part of the Palmyra Museum’s collection or of one of the previously explored burial tombs or if they were uncovered during illegal excavations.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

Looking for the Source

The Idlib Antiquities Center and in collaboration with the Syrians for Heritage Association (SIMAT), launched a research to identify the objects and to verify their provenance. In this re

search, the team reached out to Syrian and international archaeologists who are specialized in the Palmyrene antiquities in order to assist us in determining the source of these objects. Thanks to the Danish researcher Dr. Rubina Raja[3], we were able to identify the objects and to certify that six of these objects belong to the Artaban tomb in the city of Palmyra. These six artifacts were among the twenty-two archaeological objects that were looted from the tomb in 2014. The remaining object, on the other hand, belongs to another tomb in Palmyra that we have not been able to identify yet.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

The Syrian General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), on its official website[4], published on October 31st, 2014, a report on this seventh object, which was lost from the aforementioned tomb. Additionally, the INTERPOL’s website enlists within its database of the missing archaeological objects an illustrated report of seven looted artifacts, six of which match the objects that we had confiscated. We have contacted the INTERPOL in order to confirm that we have these missing artifacts and to learn more about the actual number of the stolen objects.

[3] Many thanks go to Dr. Olympia Bobou (assistant professor) and Prof. Dr. Rubina Raja (director of project) as well as the Palmyra Portrait Project team for their help in verifying this report’s data and in providing us with their database of the Palmyrene sites: https://projects.au.dk/palmyraportrait/.

[4] The General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums Website, Tomb of Artaban Report’s Link: http://goo.gl/DhbfgJ

Till Until the moment, it remains unclear whether the list includes all the Artaban tomb’s objects that the DGAM announced missing, or that report includes only six objects, and why?

Did the directorate manage to recapture the rest of the objects during the period between the end of 2014 and 2019? We are currently working to clarify this issue. It is important to mention that the DGAM announced previously that it had recaptured a large number of Palmyrene looted artifacts, but we do not have an accurate report about the recaptured objects.

image from: https://www.obs-traffic.museum/sites/default/files/ressources/files/INTERPOL_Poster_Palmyra_2017.pdf

Recently, Al-Araby TV had streamed a documentary titled “Theft of Zenobia”[5], which investigates the looting of the Artaban tomb in Palmyra. The documentary displayed still images of a looted artifact from the aforementioned tomb that was located in Turkey, and it was photographed by the channel’s team on 26/08/2018.

By comparing the photos, it became clear that this same artifact was one of the objects that Idlib Antiquities Center photographed in 2016 in Syria. Unfortunately, this object is not one of the looted busts that the team had confiscated.

[5] Al Araby TV, the Investigation Press Report’s Link: https://youtu.be/B4m_0Fbyl4s.

4. The image on the right was captured by the team of Idlib Antiquities Center, Idlib 2016. The image on the left was captured by Al Araby TV, Turkey 2018.

The Tomb of Artaban

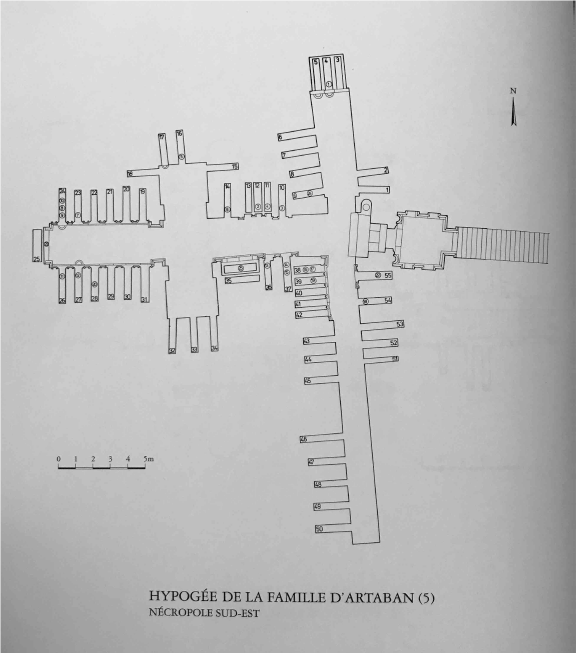

It is one of the tombs located in the southeastern Necropolis and is known as tomb No. 5. It is one of the underground funerary tombs which includes a burial chamber that was carved in the rock, and it was later built and equipped with all the necessary facilities.

It is a family tomb, like many tombs in Palmyra, that was established by Artaban as an underground tomb for him and his family. It can be accessed from the outside via a staircase that leads to a door. After entering the door, the tomb becomes divided into three sections: two passages, one on the right side and another on the left that contain several graves. There is a third passage on the axis of the door, which leads to a hall. In the middle of this third passage and on both of its sides, there are two halls of quadrilateral floorplans, which were burial chambers as well.

Artaban tomb was discovered in 1958 by the DGAM with twenty-five archaeological artifacts inside it. Twenty-two of these artifacts were relief busts, and the remaining objects were a funerary monument, a sarcophagus and an obelisk, and they were all preserved inside the tomb after it was restored by DGAM.

The Palmyrene inscriptions on these busts do not mention any date, therefore, it is difficult to precisely determined the date of when the tomb was built. By comparing the style of their sculpting, however, it is believed that the tomb was built by Artaban “Son of Ogâ” at the beginning of the Second century A.D.[6]

The floor plan of Artaban Tomb

(© A. SADURSKA, A. BOUNNI 1994)

[6] A. SADURSKA, A. BOUNNI : Les Sculptures Funéraires de Palmyre, Rome 1994.

Conclusion

In spite of locating and repatriating many of the looted Syrian antiquities, the importance of this specific mission in confiscating the funerary busts lies in the role played by the local community in collaboration with several civil institutions and the local authorities to save these artifacts. The media outlets, such as Al Arabi TV, had also played a great role in exposing the antiquities trafficking networks, and they may have indirectly contributed to halting the selling and trafficking of the rest of the objects. Together these efforts -through the work of Idlib Antiquities Center team which started in 2016- succeeded in saving these Palmyrene funerary busts.

We hope that this work will push towards the issuing of new laws that can actually protect the cultural heritage of the country and prevent its selling illegal trafficking. Through this work, we also emphasize the significance of the role of the local civic organizations and NGOs that are run by experts in the field. We call to grant them an effective role in protecting and preserving the cultural properties and to facilitate their communication with international institutions and parties that are active in the same field.

We hope that this report will shed light on the importance of saving the looted Syrian antiquities and the efforts paid to preserving them. We also hope to know the fate of the missing busts from the Tomb of Artaban, and to identify the bust No. 7, which remains unknown.

List of Confiscated Objects

Figure (1)

Title: Loculus relief with two women, Berretâ and her daughter Martâ.[7]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.50 × 0.42 × 0.27.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 100-130 CE.

General Observations: Plaque was found on this object in addition to scratches on some parts of its surface.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[7] References: Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 32, cat. 31, fig. 13; Maura Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra”, American Journal of Archeology 114 (2010), 631–661, esp. 644, appendix 1, cat. 10, 650, appendix 4, cat. 35; Signe Krag and Rubina Raja, “Representations of Women and Children in Palmyrene Funerary Loculus Reliefs, Loculus Stelae and Wall Paintings”, Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 9 (2016), 134-178, esp. 159 n. 15, 159 n. 19, 159 n. 32, 159 n. 36, n. 40, 36 nn. 42-43, 36 n. 45, 36 nn. 52-54, 36 n. 59, cat. 2; Dagmara Wielgosz-Rondolino, “Orient et Occident unis par enchantement dans la pierre sculptée. La sculpture figurative de Palmyre”, in Michel Al-Maqdissi and Eva Ishaq (eds.), La Syrie et le désastre archéologique du Proche-Orient, “Palmyre cite martyre” (Beirut, 2016), 66-82, esp. 70–71, fig. 5; Signe Krag, Funerary Representations of Palmyrene Women. From the First Century BC to the Third Century AD (Turnhout 2018),

39 n. 129, 75 n. 62, 78 nn. 89-91, 79 n. 98, 79 n. 103, 80 n. 109, 95 n. 2, 107 n. 107, 115 n. 63, 179, cat. 54; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 80 n. 87, 49 n. 105, 50 n. 119 n. 123 n. 125, 62, cat. 61.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2654.

Figure (2)

Title: Loculus relief with a priest: Shallamalat.[8]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.54 × 0.42 × 0.30.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 170 and 200 CE.

General Observations: None.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[8] References: Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 28-29, cat. 23, fig. 70; Maura Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra”, American Journal of Archeology 114 (2010), 631–661, esp. 655, appendix 5, cat. 28; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 39 n. 15, 48 n. 94, 62, cat. 60.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2646.

Figure (3)

Title: Loculus relief with male: Šamšigeram.[9]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.57 × 0.45 × 0.19.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 130 and 160 CE.

General Observations: None.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[9] References: Katsumi Tanabe, Sculptures of Palmyra, I (Tokyo 1986), 31,pl. 234; Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 26-27, cat. no. 20, fig. 29; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 88, 50 n. 121 n. 123, 62, cat. 63.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2643.

Figure (4)

Title: Loculus relief with female.[10]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.51 × 0.47 × 0.20.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 200 and 220 CE.

General Observations: Minor scratches appear on the lips and the nose.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[10] References: Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 34-35, cat. 36, fig. 178; Maura Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra”, American Journal of Archeology 114 (2010), 631–661, esp. 644, appendix 1, cat. 10, 650, appendix 4, cat. 35; Signe Krag, Funerary Representations of Palmyrene Women. From the First Century BC to the Third Century AD (Turnhout 2018), 55 n. 275, 59 n. 325, 61 n. 335, 101 n. 58, 104 n. 83, 325, cat. 596; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 80 n. 86, 49 n. 105, 63, cat. 68.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2659.

Figure (5)

Title: Loculus relief with female: Berretâ.[11]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.66 × 0.45 × 0.21.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 100-130 CE.

General Observations: Minor scratches appear on her face and right shoulder.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[11] References: Katsumi Tanabe, Sculptures of Palmyra, I (Tokyo 1986), 31, pl. 233; Anna Sadurska, “L’Art et la société: Recherches iconologiques sur la sculpture funéraire de Palmyre”, Archaeologia 45 (1994), 11-23, esp. 11, 16, fig. 2; Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 33, cat. 33, fig. 136; Dagmara Wielgosz-Rondolino, “Orient et Occident unis par enchantement dans la pierre sculptée. La sculpture figurative de Palmyre”, in Michel Al-Maqdissi and Eva Ishaq (eds.), La Syrie et le désastre archéologique du Proche-Orient, “Palmyre cite martyre” (Beirut, 2016), 66-82, esp. 70–71, fig. 5; Signe Krag, Funerary Representations of Palmyrene Women. From the First Century BC to the Third Century AD (Turnhout 2018), 35 n. 100, 39 n. 129, 95 n. 2, 105 n. 85, n. 87, 115 n. 63, 181, cat. 59; 4; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 80 n. 90, 49 n. 105, 62, cat. 57.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2656.

Figure (6)

Title: Loculus relief with priest: Yaddai.[12]

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.51 × 0.46 × 0.27.

Find Spot and Date: From the hypogeum of Artaban, in the southwest necropolis.

Period: The relief is dated between 170 and 200 CE.

General Observations: Minor hairline cracks appear on some of its parts.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center

[12] References: Katsumi Tanabe, Sculptures of Palmyra, I (Tokyo 1986), 31, pl. 236; Adnan Bounni, “Palmyre et les Palmyréniens”, in Jean-Marie Dentzer and Winfried Orthmann (eds.), Archeologie et Histoire de la Syrie II” (Saarbrücken, 1989) 251-282, esp. 260, fig. 40a; Anna Sadurska and Adnan Bounni, Les sculptures funéraires de Palmyre (Rome, 1994) 26, cat. 19, fig. 83; Maura Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra”, American Journal of Archeology 114 (2010), 655, appendix 5, cat. 27; Signe Krag, “Palmyrene funerary buildings and family burial patterns”, in Signe Krag and Rubina Raja (eds.), Women, children and the family in Palmyra (Copenhagen, 2019), 38-66, esp. 47 n. 86, 63, cat. 67.

Inscription: Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini, Palmyrene Aramaic Texts (Baltimore, 1996), no. 2642.

Figure (7)

Title: Funerary relief of a woman.

Material: Limestone.

Dimensions: 0.54 × 0.46 × 0.25.

Find Spot and Date: Originally from Palmyra but no further information about its find spot or date.

Period: Unknown.

General Observations: None.

Photo credit: Idlib Antiquities Center